"Community Wisdom Bank" is a community site to share the "wisdom" with people

around the world and to create a sustainable world!!

- 8-point Traditional Japnaese Wisdom

- Interview with Saburo Kato

Interview with Saburo Kato

|

President, JAES 21 Saburo Kato |

Japan in the Edo period (1803-1867) had an economy that fed 30 million people, although the words of that era's influential philosophers and economic thinkers such as Sontoku Ninomiya (1787-1856)✱1 and Baigan Ishida (1685-1744)✱2 would not resonate with the logic typically found in modern economic textbooks.

Edahiro: What is economic growth?

Kato: First, let me clarify the term "growth." I think "growth" and "economic growth" are completely different.

My third grandchild was born last summer, and the baby is absolutely adorable. The growth and development of grandchildren is wonderful. It is great that children not only grow physically, but also mentally and spiritually.

So, I don't think "growth" itself is necessarily bad. "Economic growth" is in fact mostly about gross national product (GNP). We talk about GNP growth of 3 percent and so on.

I believe that the specific central components of GNP are "production" and "consumption." If someone asks me, "What is economic growth? What is growing?" I would say it is a materialistic increase of production and consumption, expressed in monetary terms.

Edahiro: Is economic growth something desirable?

Kato: Both in Japan and the U.S., some people live under conditions that are not sufficient to maintain human dignity. Generally, in poor and developing countries, human dignity is undermined by food shortages, a lack of access to drinking water, and very poor sanitary conditions of housing. I think economic growth is desirable in such places.

In industrialized countries including Japan where material conditions are very much better satisfied, however, I don't think it is desirable. Obviously we don't need to wait for the results of analysis such as our "ecological footprints" to realize that the ecological environment is highly degraded.

In other words, the global environment itself is overpopulated. According to climate change science and analysis such as the ecological footprint, humanity's footprint exceeds the Earth's capacity by about 50 percent.

Since about one billion people, especially in industrialized countries, are quite satisfied materially under these circumstances, I hardly think that it is desirable, necessary or possible to pursue further economic growth in these countries.

Edahiro: By saying "not necessary or possible" you already answered my next two questions ("Is economic growth necessary?" and "Is it possible to continue economic growth?"), but do you have any additional comments?

Kato: As I said, economic growth is not absolutely necessary in affluent societies that have already developed. Even in affluent countries, however, human dignity is not being maintained for quite a lot of people.

For example in Japan, many households with single mothers, have annual incomes below two million yen (about U.S.$16,800). In some households, the mother and/or father work to exhaustion to make ends meet, so it would not be ethical to make a sweeping statement to them that economic growth is not necessary.

But when we look at Japan and industrial countries as a whole, obviously we are in a situation of being saturated. For them it is rather a matter of distribution. Due to inadequate distribution, quite a lot of people in Japan have annual incomes of less than two million yen, and the number of people like this is increasing.

In the U.S., more and more people are conscious of the 1% ultra-rich versus the remaining 99%, and feel that they are the 99 percent. We need to look at this as a problem of distribution.

Furthermore, globally, more than one billion people are still living in extreme poverty. It is not ethical to expect them to agree that economic growth is not necessary.

This is also a matter of distribution for human society as a whole, just as it is in Japan, because obviously we are becoming more and more affluent materially, at global level.

Therefore, at international conferences -- for example on climate change issues, and a recent UN meeting on disaster prevention -- one of the major issues is naturally about how to distribute financial resources and technology between developing and affluent countries.

Edahiro: Is something sacrificed in order to sustain economic growth? And if so, what and why?

Kato: There are sacrifices in many areas. But before I talk about that, let me add that the "distribution" I just mentioned is actually a difficult task. It is politically and philosophically challenging.

Edahiro: Philosophically? What kind of challenges?

Kato: In the past two centuries or so, humanity, especially mainly Western societies, have put a very high priority on "freedom." Besides freedom of thought and speech, the freedom of political association, and for the choice of what kind of businesses you do, freedom has also been given the greatest emphasis.

To maintain that freedom, the freedom of competition was empowered. People are told to make an effort freely within the concept of "free competition" and "freedom." Those who can run fast can advance themselves. Those who don't make as much effort or who lack the ability might fall behind, but that is just the way it is. That's what "freedom" and "personal responsibility" are all about. That's the thinking.

On the other hand, people like Professor Thomas Piketty, who recently has been very popular in Japan, claim that focusing too much on freedom leads to greater inequality, and that this has been the case especially since the start of the twentieth century. He calls for a global tax on the wealthy and as much as possible, diverting the tax revenue to help the poor as much as possible.

Others, such as the typical Republican supporter in the U.S., argue that ideas like Piketty's are wrong, because nothing is more important than human freedom. They would assert that there should be no limits on freedom, and it is unacceptable for governments to interfere with or restrict those who have become rich as a result of freedom.

Such a mindset is also found in Japan today. Though not as extreme as U.S. Republicans, some people here insist that personal freedom is essential, and that it should not be limited. Therefore, taxing the rich is also vigorously opposed in Japan, and these people say the rich would leave the country if we do such a thing. They are mired in this kind of discussion.

In any case, "distribution" in the sense of seeking "appropriate distribution" is also politically difficult. Especially, democratic politics nowadays are becoming quite unreliable -- which I think is a very critical point -- so I can't help thinking that it would be difficult to achieve fair distribution.

The reason is that the rich lobby to protect their interests. I never thought that lobbying itself was bad, but especially in American politics, the spending of enormous sums of money for lobbying has become a dominant driving force. The U.S. Supreme Court held that political funding should not be limited, and those who want to offer money should be allowed to do so without restriction. The idea is that if a donation is to express one's thinking and sentiments, what is wrong with providing unlimited funding to politicians who match one's interests? This stance is one of the consequences of such a heavy emphasis on freedom.

One of the outcomes, on the issue of climate change, is that oil and coal industries give generous political donations, lobby their representatives and actually spend money to spread skepticism and delay the necessary actions. Gun control is another example, and a recent example is the politically powerful and rich Jewish community in the U.S. lobbying to support Israel.

As a result of this kind of thing, parliamentary democracy, which was often considered to be ideal as a political form, ends up being significantly distorted.

In Japan, but not quite as much as in the U.S., politics is now being distorted. In Europe as well, it may not be as obvious as in the U.S., but there are various problems.

In that sense, when we look back, we can understand that the problem is that a policy to redistribute income by progressively taxing the rich has become more difficult to be implemented.

With these circumstances in mind, I think about how it was during the Edo period. I don't think the idea in the Edo period was to let the rich and powerful continue to grow, and to leave the poor and powerless to die. There was a spirit of helping and sharing.

Belief systems such as Confucian ethics and Buddhism influenced the spirit of sharing in this era. An example is Yozan Uesugi (1751-1822)✱3, a politician who was appointed at a young age as a feudal lord to the Yonezawa Clan, which at the time was in financial turmoil, in today's Yamagata Prefecture. Back then, lords generally had a luxurious life, but he was determined to "eat only one soup and one side dish."

In short, he didn't have the thought of his own freedom as "I am the lord and I can do anything I want," but rather as a lord, he consciously and ethically "redistributed" incomes, as we might say today, in order to stabilize the lives of his people.

He wasn't unique in Japan. There are many similar cases. Yozan Uesugi was a typical example among them.

In slightly more modern times, Sontoku Ninomiya was not a lord but in fact, in an ordinary class, and he devoted himself to help those who were powerless and weak, making it a principle to save money and develop new fields to grow rice.

On the other hand, there will be a wider gap if we fundamentally support "freedom" and "free competition" saying that "there is nothing wrong about powerful people becoming more powerful" just like in the U.S.

It is a competition just like the sport of sumo. One wins and the other loses. No matter how many people are involved -- 3,000 or 10,000 or one billion -- ultimately, only one can win after intensive competition. The rest is a heap of losers.

But the political ideas and ethical views of Japan during and before the Edo period were different. It wasn't like "the most powerful people can win as much as they want."

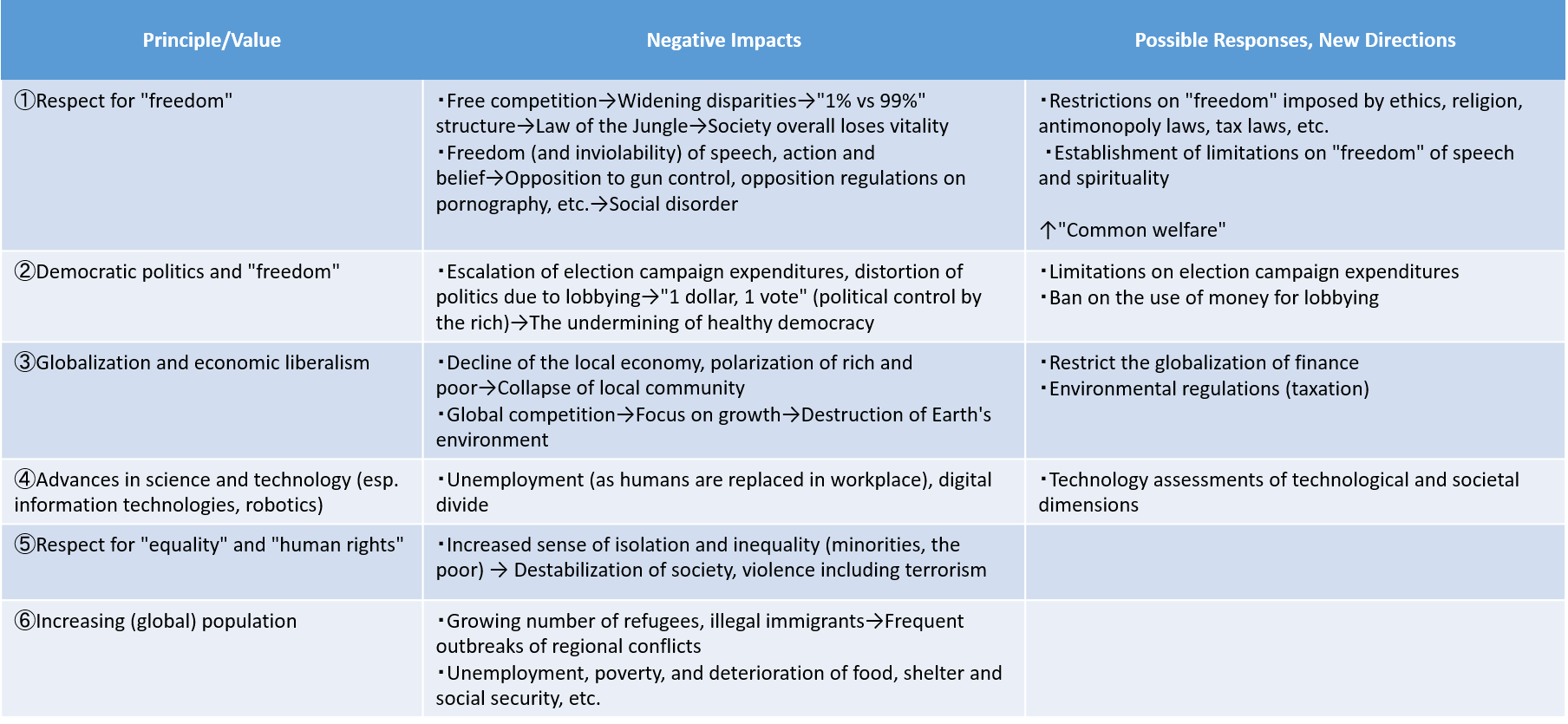

That is why I am interested in the ethics and thinking of the Edo period. I brought a chart (Figure 1) here to explore the wisdom of the Japanese people during and before the Edo period and to revisit the view of economic perspectives and concepts of ethics that have been created by the Western world over many centuries.

Figure 1: Factors that have caused severe hardship in the world today

The respect of freedom has been considered to be good. I don't mean to deny that in itself. Democracy is very valuable. So are globalization and scientific and technological development.

But I think this has all resulted in the impacts shown in the chart. It is not as simple as stating "freedom brings these," but the free competition that comes with these things creates a world where those in power win and disparities are widened. In the U.S., it is the structure of the one percent versus the 99 percent. In the capitalism-based current economy, we see the situation frequently raised by Professor Piketty. It is the law of the jungle. Consequently, the vitality of the society as a whole suffers, creating a lot of poor people, a heap of losers. Society as a whole loses vitality and becomes impoverished.

Freedom of speech and freedom of expression are of course essential, but a fundamentalist approach can lead to people to believe statements like, "It's crazy to control guns." "What's wrong with owning a gun?" "We need to carry guns in this increasingly dangerous world." If someone says, "I want to be naked," people may say, "Nothing's wrong with being naked." "Let them walk naked in the streets if they want to. They should be free to do so."

Continuing this kind of argument may result in disrupting the social order and stability. In short, recently I strongly feel that we may need to reconstruct the "freedom" and "democracy" which have been seen as good things until now.

"Jiyu to Minshushugi wo Mo Yameru" (Giving up on freedom and democracy), a book written by Professor Keishi Saeki of Kyoto University, is very interesting. At a glance, the title may imply that the author is a radical and odd person. Like others, I thought he was quite bold to say, "Let's give up on freedom and democracy."

But of course, he is far from being insincere. The book points out the problems caused by "freedom" and some sort of limitations of "democracy." I don't completely agree with Mr. Saeki, but realized that there was someone ahead of me at least who said the things like this.

Edahiro: This is a very important table. It also states possible responses and new directions. We need to work on these from now on.

Kato: As I mentioned, I am not saying that "Freedom is no good. Dump it." Neither am I saying that democracy is "not good."

But if we don't do anything about this situation, we will face many problems, which are deeply related with the problems of today's topic, economic growth. So we need to think.

Let me go back to the story about the things we must sacrifice for economic growth. There are already many sacrifices.

The humanity-wide pursuit of economic growth has resulted in us exceeding the environmental carrying capacity of the global environment. This is well-known by clear analysis of our ecological footprint. You may have heard how many Earths we would need if seven billion people lived like people in the U.S. or Japan.

Having already exceeded the environmental carrying capacity of the Earth, what exactly has happened? Vivid consequences are climate change, a dramatic loss of biodiversity, and traces of chemicals absorbed everywhere.

Reading about micro plastics made me think recently. Plastics making their way into the oceans continue to break down in the water into particles through a kind of chemical reaction, weathering, and exposure to light. The particles are absorbed into living things such as fish. This is another chemical pollution problem. We have a number of such problems and they are increasing.

Another cost is the social disparity between poor and rich, which is a societal problem. The gap between rich and poor has existed in every period of history, and the Edo period was no exception. But I think the gap was within an acceptable range.

The current poor-rich gap, however, shows many poor people unable to maintain human dignity. Even now in the twenty-first century, for example, some don't have electricity. Lack of electricity is not so bad, but many people don't have access to safe food and water, and many are living under very bad sanitary conditions.

On another front, during this era when some people live in poverty, others are extremely wealthy. We often hear that CEOs of major U.S. companies are getting paid more than 200 times more than the average worker. But some even say that this is still not enough.

When I consider this, I feel that it is not a matter of simply accepting rich people making more or feeling sorry for poor people. Rather, the stability of society as a whole is at stake. For example, more and more young people are attracted to terrorist groups including an inhumane group, Islamic State. In Europe, the unemployment rate among young people is around 20 or 30 percent, and nearly 50 percent in Greece and Spain.

When it comes to that, it is not possible to maintain the social order. We can't just leave young people with no place to work and say, "They are unemployed because they didn't work hard enough. I am working hard, so I deserve to make money. People are free to do what they want." This situation causes significant damage to inclusion and the value of human society.

Furthermore, I think the spiritual and cultural damage is significant. Spiritual in this sense means religious value and a sense of morality. We have been focusing on economy and expanding globalization under free competition. In addition, disruptive technologies have developed so quickly that spiritual and cultural aspects are unable to keep up. I think these are extremely serious issues.

So the costs or sacrifices are exceedingly large. Although a handful people are rich, the power of society as a whole is declining.

Reading books by Professor Joseph E. Stiglitz in the U.S., we see that he is deeply concerned about the overall losses occurring in American society. While there are extremely rich people like Bill Gates, there are also many poor people, many cannot maintain a household, and communities cannot be maintained as well. So seen as a whole, society is deteriorating in the U.S. It really made sense to me.

So now, how about Japan? I think the economic growth policies being implemented now are only creating households that will depend on social welfare in the future. For example, many young people are hired as non-regular employees and they are not provided adequate training. It is a temporary workforce. But still those who have jobs may not be so bad off. Some people don't even have jobs. Public education also has more and more temporary teachers, which may lower the quality of teachers.

In other words, when people in their tens and twenties now reach their fifties, sixties or seventies and don't have a way to make living, I think they will rely on some form of support, such as a social welfare. As the number of people relying on social welfare increases, the vitality of society as a whole will be drastically reduced.

If we compare now with the time from the Edo to Meiji periods, I think the quality of life in terms of GNP was extremely low back then. But I believe Japanese society put a priority on education. Children were sent to study at terakoya (small temple-run schools), and their development as persons was nurtured in many ways, as expressed through common sayings of the day about being satisfied and grateful for what you had (e.g., "taru wo shiru," or "know that you have enough"), about proper conduct, and about respect.

After the Meiji Restoration (which restored imperial rule in 1868 under Emperor Meiji), new and Western ways were rapidly introduced to Japan, upon the solid foundation of the Edo period. Japan absorbed it well and grew. In a short time, Japan transformed itself quite smoothly from a feudal to a modern system.

In postwar years, many people still maintained a strong spirit even though much of the country had been reduced to ashes during the war. That's why people had the power to rise up again.

But if we continue the current policy of "Rich people, get richer. Poor people, too bad, but you deserve to be poor because you didn't work hard enough," Japanese society may be filled in 20, 30, or 40 years with people unable to support themselves, and a country lacking a sense of ethics. As a result, I think the overall vitality of society will slide dramatically.

When I read "The price of inequality" by Stiglitz, at first I didn't understand it well, but after I thought about it more, I was able to see his point. It is very important to know that the outcome will be like that if we leave free competition to operate with no controls.

Edahiro: My next question was going to be, "If there is something Japan has lost due to continued economic growth, what is it?" But you have just answered that one. So next, especially on the environmental front, you have spent your time on the side of developing measures to respond to the problems, correct?

Kato: Yes, I have dedicated myself to working on environmental issues since my younger years until now, for a half century -- 27 years as public servant, and 23 years on the non-profit and non-governmental side.

Edahiro: This will be my last question. How should we view the relationship between economic growth and a sustainable, happy society?

Kato: Basically, when we look at the twenty-first century as a whole, these two are obviously in complete conflict with each other.

In rich countries, however, there are also poor people. Human society with seven billion people has really poor people, indeed. For them, some degree of economic growth is of course necessary. However, humanity is already beyond the environmental carrying capacity of the Earth as a whole.

We have only two paths left. One leads to total collapse and catastrophe.

The other path does not lead to collapse. People in developed countries, including Japan, learn to accept some degree of inconvenience and a lower material standard of living, and redirect some money to the poor both domestically and globally. And in its totality, humanity manages to live just within the carrying capacity of the Earth.

If we can create such a world, economic growth can be adequately realized, with an emphasis on quality and on creating a sustainable and happy society. However, if we think it will be very hard to reach that point both politically and socially, that means that these two things are basically in conflict with each other.

Edahiro: With an awareness that we need to re-create the economy, I have interviewed 100 people. Mr. Kato, what do you think about that need? With your background of working in the environmental field for a long time, do you think economics is a big problem?

Kato: I read the booklet you wrote with Herman Daly, titled "Teijokeizai ha Kanouda" (A Steady-State Economy Is Possible), with great interest. I have also read your previous books many times.

The only thing I regret is that even though Japan had wisdom during the Edo period such as the spirit of "taru wo shiru" (know that you have enough), Western academics don't mention it. Perhaps it has been difficult to explain the wisdom of Japan's traditional society in terms of Western logic.

An economist once told me, "Mr. Kato, you shouldn't use that saying. Unless an idea can be shown by mathematical formula, it is not academic, it is meaningless." He could speak his mind because he knew I trusted him. He said that ideas about economics based on sufficiency and harmony were not academic.

So next, let's ask what Western economics have produced. It is well known that Adam Smith started his learning from moral philosophy. From moral philosophy he came to be known as the founder of market economics. John Maynard Keynes probably never had such nonsensical thoughts that economics could solve everything if only you could express it with a mathematical formula.

Japan in the Edo period lasted over two centuries with no major war and at the same time the culture and arts flourished. During that time, the population grew from 10 million to over 30 million.

Of course, if we look closely, we could probably find that there were problems, including the suppression of human rights. There was no freedom of speech to criticize authority. There must have been violations of human rights, such as infanticide and abandoning of elderly women in distant mountains to ensure the survival of other family members. However, overall the Edo period was peaceful as well as spiritually rich, and a sustainable society was maintained for a long time. So I believe that we can learn much from their wisdom. I think we should try again to explain these ways of thinking, but with Western logic and language so that people in the West can understand.

As far as I know, some scholars do study the economics of the Edo period, but they have no connection with Western economics.

Again, the writings and arguments of Japanese philosophers Sontoku Ninomiya and Baigan Ishida, for example, would not fit into the logic of economics textbooks, even if we were to translate their ideas into modern languages. Even so, the reality is that the "economy" of the Edo period was able to feed 30 million people. On the other hand, what has Western economics brought to the world? We have a human society that is currently unstable and has lost its sustainability. What do people think about that? Is the economics you know the only way things must be?

I wrote an essay entitled "Why Japanese people cannot receive the Nobel Prize in Economics?" for the December 2012 issue of our organization's newsletter magazine, "The Environment and Civilization." Japanese have received the Nobel Prize in physics, chemistry and literature, but not in economics. The reason is that Japanese scholars have to scramble just to follow and explain the philosophies of Western economists like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and recently, Herman Daly and Thomas Piketty.

I think that is a very important point. I am not a scholar, so I don't know the logic and language of academia, but I am interested in pursuing Japanese traditional wisdom in the context of the values of today.

Herman Daly received the Blue Planet Prize from the Asahi Glass Foundation. Whenever I go to the Blue Planet Prize Commemorative Lecture, held at the United Nations University (in Tokyo), I always ask a question to the speakers. I missed Herman Daly's lecture but if I had been there, I would have asked him, "Your three principles are of course superb, but do you know about Japan's wisdom of sustainability in the past? Do you have any comments on that?" Ms. Edahiro, please ask him for me.

Edahiro: He may not know about that history.

Kato: Yes, perhaps not. The works of Hokusai and Hiroshige, prominent Japanese artists of the past, had a great impact on Western art. Their influence on Western artists is more than we could imagine. In recent years, Japanese food and even sake are appreciated around the world. This is because words are not necessary for them.

On the other hand, economics and economic thought are impossible to convey without words. Just by drawing one picture, no one could instantly make someone understand Adam Smith's economic theory.

Neither Smith, nor Ricardo, nor Piketty would understand Baigan Ishida's words, even if they were in a language that is understandable for them, because the logic is completely different. So we need to re-construct Ishida's words from an economic viewpoint. Japanese economists have not made much effort for that, which is very disappointing to me.

With that in mind, I once sent letters to several prominent economists, but no one replied to me.

I am not disappointed about getting no replies. Perhaps they could not understand what I meant. It is natural that they thought the principles of the ancient Edo period could not be part of academic learning, because they had no systemic approach and statistical data, and it would difficult to show numbers. This is how I've understood Japanese economists' way of learning.

Ms. Edahiro, you have a chance to communicate with these people, including people outside Japan.

Edahiro: You are right. Some astute people in the West have realized that they cannot find enough answers in Western thought, so they seek answers in the East, for example, in the study of Zen or Buddhism. Many have mastered the principles even more than Japanese. I have long been wanting to study Baigan Ishida and others properly, but it has been hard to find a good teacher or a book that can help a layperson like me understand the principles. For Sontoku Ninomiya, many books have been published, but has anyone studied him from an economic standpoint or with an economic approach?

Kato: From an economic viewpoint, almost nobody does. Of course, some Japanese scholars fervently study Baigan Ishida or others, but those scholars don't see them from an economic viewpoint.

On the other hand, researchers in the area of economics, such as environmental economics and related fields, just follow the teachings of Herman Daly and others. They don't have any connection with their Japanese predecessors.

Edahiro: Would it be possible to connect the two by holding a study session? It is very important, indeed.

Kato: I think this is what Japan can contribute most to the world. I do not intend to boost it as is "Japan is superior" or "Baigan Ishida is amazing." However, the Western side of social sciences, including Western-oriented economics, honestly, is collapsing as a result. From an academic perspective, the logic may have not been collapsed. The way society operates, brought on by Western social sciences, is collapsing, though.

On the other hand, economics in the Edo period -- though there may have been no term for "economics" at that time -- does not match the path of Western academic tradition, which has evolved since ancient Greece, meaning first establish clear definitions, then the axioms and principles, then build the hypothesis, and then demonstrate it.

The contrast is like oil and water. I want to mention, however, that ultimately, the thinking in Japan might have been better than the Western way of thinking. Western economics is superbly organized as learning and systematically well-established. But the outcomes they have brought to the world are disorder and unhappiness. Freedom, equality and human rights are all good in themselves. But what the Western way of thinking has brought to the world in the twenty-first century has been dismal, hasn't it?

That's why we should review the learning, principles and philosophy brought from the West. As you said, of course some people understand the issues very well, even in the Western world.

We can start with something like a small study session. The green economy initiatives that we are starting to deal with are part of that discussion. The green economy that we have been thinking about has been developed by environmentally conscious people generally centering around Tokyo. So when we take it from Tokyo to other areas, it may not be well received by local people, who may not get the point.

I want to see the reactions of the heads of small- and medium-sized companies in local areas, who are struggling with the management of their businesses. How do they see the green economy? Will they see it as just a pastime of intellectuals? Those are the things I want to focus on.

But I don't have much time, because I am 75 years old. So I want to pass it on to younger people, including my colleague, Ms. Konoe Fujimura, who is a co-representative of my organization and 10 years younger than me, and you, Ms. Edahiro, who are much younger than us.

Especially, you have extensive contacts with the international community, so I would certainly like to see you involved in this. The people you are associated with are all excellent cultural figures in the West. I believe they can understand what we want to convey.

Edahiro: I have been engaged in sending out Japanese information to the world from my organization, Japan for Sustainability. The most valued and shared articles were the stories on the Edo period. We wrote twice about the Edo period, and those articles received a great response from the readers, who wrote back recognizing that Japan had a sustainable society in the Edo period, something they had been looking for. The articles are based on Eisuke Ishikawa's book about the Edo period, when Japan was a plant-based country that co-existed with and depended on plants for the production and recycling of everything. As with Sontoku Ninomiya and Baigan Ishida, I need a teacher who can explain economic aspects of their philosophy, so I will look for one.

Kato: As far as I know, there are very few of them. Of course, a lot of people study Sontoku Ninomiya and he has a big group of fans. There are also many people who study Baigan Ishida. However, very few people think of the combination of Baigan Ishida and Adam Smith based on the perspectives we have discussed today.

Edahiro: Recently while I was talking with Herman Daly, he said that university students of economics do not read Adam Smith today, and never touch upon the steady-state economy, and so on. This is because they start their study of economics from neoclassicism.

Kato: Especially in the U.S., yes. I don't know the situation in Europe, but it is serious in the U.S. I don't think intellectuals follow the trend, but overall, American people put the priority on freedom, with freedom of money included.

Joseph Stiglitz says that the American democracy today is getting to the point of one dollar, one vote, rather than one person, one vote. If things continue this way, that will be the reality.

Japan is not as extreme as the U.S. in this regard, but indeed it has moved in this direction to some extent.

Edahiro: Recently in Europe, some groups and networks are working to re-design the economy. I would like to explain Baigan Ishida there, and study with them. But first, I need to study Ishida myself. I will think about who can help me.

Kato: I sent you my book, titled ''Taru wo Shiru' Ikikata no Susume: Kankyo no Shiso" (Environmental Thought -- Some Suggestions for the Lifestyle of Sufficiency). The book covers exactly what you just mentioned, so please have another look at it. I introduce three people in the book, Shozo Tanaka, Yukichi Fukuzawa, and Soseki Natsume.

I chose them because all three were born at the end of the Edo period. Basically they received an Edo-period education. Yukichi and Soseki saw Europe and the U.S. well when they were rather young, but Shozo had never been to Europe or the U.S. He was from a rural area, but he studied traditional Japanese learning, including the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism and the like at a temple school. How these three people reacted when Western culture flooded into Japan was interesting for me, so I wrote the book from that perspective.

I don't think we need to go into flurry, but if I can, I would like to study with people who know the international world well and care about Japanese culture, such as people around you.

Now, the Western world is struggling very much. In January 2015, the Paris office of a French satirical magazine was attacked, and that is just one example. Many people may cry out that freedom of speech is absolute, but some people, including the French historian Emmanuel Todd, are doubtful about it. Can freedom of speech really be unlimited? Some people are not so sure, even in France.

The Japanese Constitution guarantees various kinds of freedom, but the proviso is "to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare." Our non-profit organization, as you may know, proposes to introduce environmental principles into the Constitution, and has been working on this for the past ten years. In the process, we debated about what is really meant by "public welfare." Our conclusion was that public welfare means to build and maintain a sustainable society, and that is what we are advocating.

Under the current Japanese Constitution, and maybe it should be similar in Europe and the U.S., I believe that the acceptance of freedom of speech and the freedom of expression should not be unlimited. The current trend, however, seems to be going in that direction (unlimited).

Pornography is one example. Even in European societies, there was a time when it was generally accepted that certain things that should not be expressed publicly should not be exposed. However, people gradually began to remove constraints, saying that this was freedom and everyone should be free to do as they like. However, if you ask whether "doing as they like" has made everyone happy, I would say the answer is no.

Similarly, we can't say "Go ahead and make as much money as you like, because you are free to do so. If you want to be poor because you can't make money, go ahead and stay poor."

In Japan, before World War II, some kind of code of conduct and moral values controlled behavior -- for example, knowing that you had enough and not living beyond your means. This is because there was a shared understanding in society that if everyone was free to do anything, humanity could go out of control.

Maybe the reason Adam Smith started his study from moral theory, though I didn't study much about him, is that he may have recognized that human beings can end up getting lost if they are left without guides, so they need some kind of control. The way of controlling and way of maintaining freedom are always in a mutual state of tension, and I think this point is important.

That is not Adam Smith's kind of language and logic, but Japanese people did have them, indeed.

Edahiro: The balance is now totally …

Kato: … breaking down.

Edahiro: Thank you for taking time for this interview. Please keep in touch.

✱1 Sontoku Ninomiya (1787-1856)

Japanese agrarian reformer in the late Edo period, born into a farming family in what is currently Odawara City, Kanagawa Prefecture. He lost his parents when young, but learned "The Analects of Confucius," "The Great Learning," and "The Doctrine of the Mean," and other greats works by himself, while engaged in hard labor helping his uncle farm. Ninomiya rebuilt his family fortunes by the time he was a young man. Later he succeeded in rebuilding the household finances of warriors of the Odawara Domain and revitalizing agricultural areas in the domain. With his original farming methods and the policies for rural revitalization (Hotoku Shihou) based on those experiences, he helped revitalize about 600 villages. In his final years of life, Ninomiya attracted a number of disciples and had significant influence on agricultural policy.

✱2 Baigan Ishida (1685-1744)

Japanese scholar born into a farming family in what is currently Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. While apprenticed to a merchant house in Kyoto as a young man, Ishida sought learning that would be relevant for daily life and work. His doctrine was based on the Zhu Xi school of Neo-Confucianism and incorporated elements of Buddhist, Shinto, and the philosophy of Laozi and Zhuangzi as well. Ishida regarded merchants, who were generally despised at the time, as ordinary people, and insisted that they were not inferior to warriors in performing a role in society. Ishida also called on merchants to reflect on themselves and articulated a code of commercial ethics by condemning unscrupulous merchants. He insisted that commercial trades should be freely conducted on a one-to-one level playing field. Ishida had a great influence on merchant society.

✱3 Yozan Uesugi (1751-1822)

Feudal lord in the middle of the Edo period. Born into the family of a minor feudal lord (daimyo) in what is currently Kyushu, he was adopted into the Uesugi family of feudal lords in the Yonezawa Domain in what is Yamagata Prefecture today, and succeeded as head when he was 17 years old. The Yonezawa Domain was in a financial crisis at that time, but Uesugi practiced simplicity and frugality himself and also encouraged his subordinates and people in his domain to practice austerity. Uesugi was known as a virtuous ruler who rebuilt the domain's finances with policies that included revitalizing farm villages and developing industry.

All Rights Reserved.